Few health challenges are as well-publicized as high blood pressure, a topic that has become all too familiar, appearing everywhere from the daily news to medical conferences. And being so familiar, it is easy to overlook the fact that most of this attention has been devoted to a problem that stems from just one side of the heart.

In fact, talk of high blood pressure usually refers to systemic hypertension, a condition that depends on how well the heart’s left side can pump blood throughout the body’s extremities. Meanwhile, the arteries and veins on the right side oversee the pulmonary flow—blood traveling back and forth to the lungs—and they receive much less attention.

The pressure in these vessels serving the lungs is just a fraction of that found in the rest of the body. The muscles on the heart’s right side work nowhere nearly as hard to maintain what is almost a passive flow. And while high pressures in this flow are considerably less common than systemic hypertension, the effects of pulmonary hypertension are no less dire.

“It’s actually a disease of the blood vessels,” explained Carolyn Pugliese, the advanced practice nurse responsible for patients enrolled in the University of Ottawa Heart Institute Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic. “We call it a disease of proliferation.”

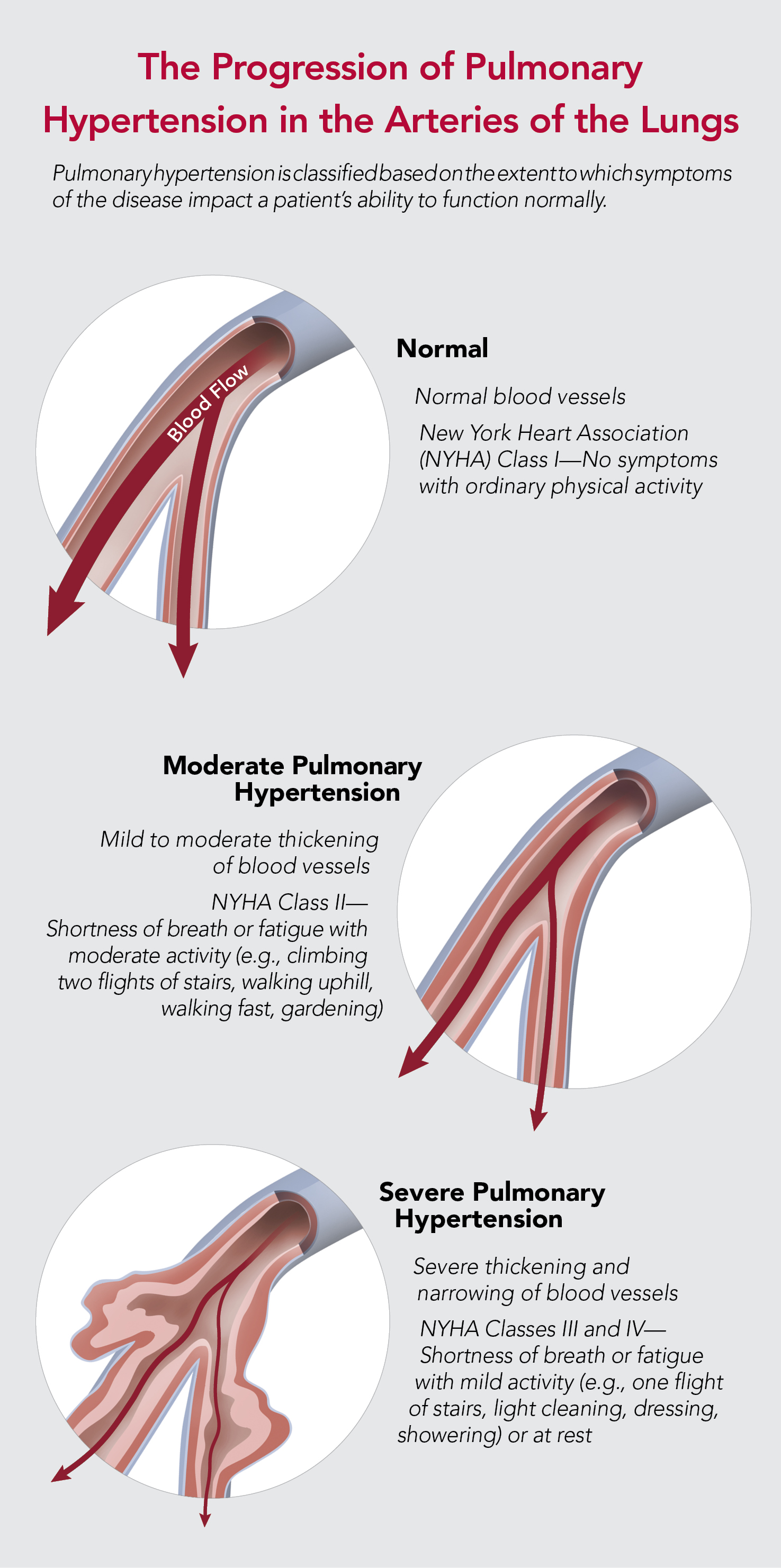

The proliferation, in this case, is a buildup of cells that form lesions on artery walls, almost blocking the flow of blood. By compromising the body’s ability to exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide in the bloodstream, pulmonary hypertension can cause shortness of breath, fatigue, dizziness, fainting, chest pain, racing heartbeat or swelling in the ankles, legs and midsection.

The condition is often overlooked in routine exams because its symptoms can have many other causes. An echocardiogram, an ultrasound of the heart, can identify the condition fairly easily by providing an estimate of blood pressure on the right side of the heart. Pugliese noted that this prospect is being considered more often, as dedicated clinics have emerged and doctors have become increasingly aware of the condition.

Pulmonary hypertension is often overlooked in routine exams because its symptoms can have many other causes.

“It’s been bumped from being a rare disease to an uncommon disease,” she said. “It’s not as common as hypertension, it’s not as common as coronary artery disease, it’s not as common as atrial fibrillation.”

This growing awareness extends to new directions in research, although Pugliese noted that the cause of pulmonary hypertension remains poorly understood. It is known to be linked with the use of appetite suppressants; HIV infection; autoimmune system disorders, like scleroderma and lupus erythematosus; and the BMPR2 gene mutation. It may also be linked to other genetic factors. Just as significantly, it is not necessarily linked with specific behaviours, such as smoking, or even the seemingly related problem of systemic hypertension.

Pugliese regularly finds herself conveying the harsh limits of this knowledge to patients who wonder what they might have done wrong. “This is nothing they’ve caused,” she said. “There’s nothing they could have done to prevent this.”

Treatment options are similarly limited, although there are an increasing number of drugs to help improve the blood flow to the lungs. Surgery can be an option if the pulmonary hypertension is caused by chronic clots in the arteries of the lungs as opposed to a disease of the vessels and the blockage in the arteries is close enough to the heart for practical access. Unfortunately, therapies for pulmonary hypertension can only manage the disease rather than cure it. For Pugliese, this shortcoming makes it all the more important to examine the source of the disease and its treatment.

She came to know systemic hypertension in her former posting at a heart failure clinic. While she knew little about pulmonary arterial hypertension, she learned quickly in 2007, when she was approached to lead the nursing component of the new clinic the Heart Institute was establishing for this disease. It is now one of 14 such clinics across Canada. The Heart Institute handles about 400 individuals with different sorts of pulmonary hypertension, and Pugliese is directly responsible for the treatment of around 115 of these patients.

She also works closely with the Pulmonary Hypertension Association of Canada, a patient advocacy organization that holds a national conference every two years to update participants on the latest developments in the field. In September, the event was held in Ottawa for the first time, with members of the Heart Institute contributing insights to an audience that is paying closer attention to this disease than ever before.

“PH [pulmonary hypertension] nurses should screen for patient and family coping at every PH clinic visit,” she wrote. “Chronic illness can vary over time; the medical regimen prescribed to the patient, the prognosis, and the functional capability of the patient will inevitably vary as well. Patients, partners and children may adapt at different rates to their situation, and the type and rate of adaptation is likely to be influenced by various factors and can lead to a divergence in quality of life.”

Her contribution was awarded first prize in the event’s poster competition, and that success inspired her to take an even more ambitious approach to improving the outlook for patients. After speaking with her counterparts at clinics elsewhere in Canada and abroad, she observed that they were operating within administrative structures that could vary widely from one place to the next. In contrast to a globally accepted model of dedicated staff at conventional hypertension treatment facilities, she has learned how dramatically the comparable facilities for pulmonary hypertension can differ.

Pugliese, therefore, plans to survey various clinics to determine how these sites are run and what their staff would suggest about how they could be run differently. This sharing of experience and best practices, which she hopes to prepare for formal publication, could set the stage for the kind of standardized treatment that characterizes the best of cardiac care—ideally leading to formal best practice guidelines (see sidebar).

With these sorts of insights captured in a clear way, she concluded, nurses like her would then have the information they require to define an organization that can support their goals and the needs of patients, which come down to day-to-day realities. “My job,” she said, “is to make sure the drugs are working, the patients are improving, their symptoms are improving, they’re getting stronger and I’m keeping them out of heart failure.”