Heart failure is a disease that challenges the patient and the health care system alike. An often progressive condition with many potential causes and no cure, it can be effectively managed. Doing so is a complex effort that requires diligence and careful monitoring, but a recent study evaluating the effectiveness of guideline-recommended therapies for heart failure highlights the importance of putting these therapies to work.

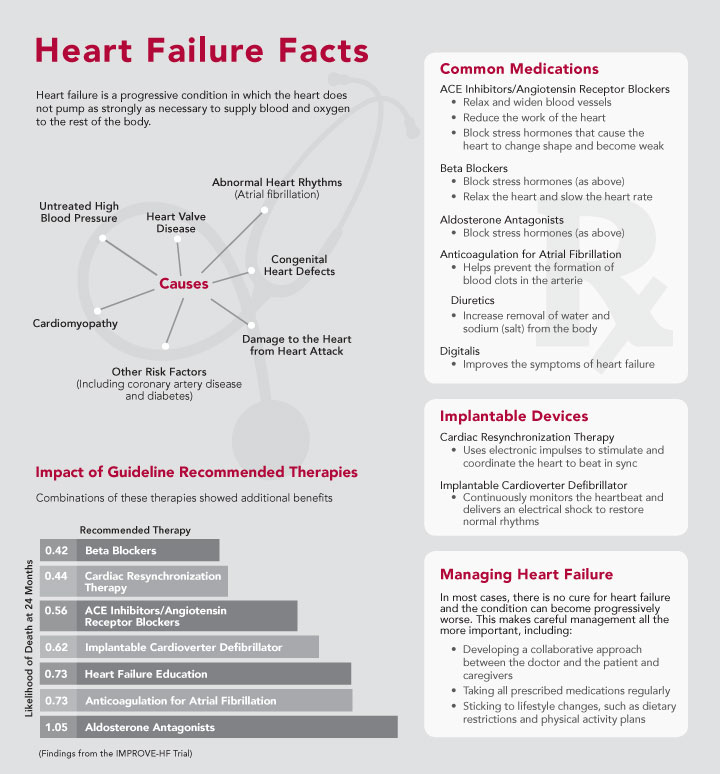

Heart attack, untreated high blood pressure, abnormal heart rhythms, heart valve disease, cardiomyopathy, and congenital heart defects: All of these can lead to heart failure by weakening or damaging the heart so that it’s unable to pump as strongly as necessary to supply blood and oxygen to the rest of the body.

With the prevalence of the risk factors and direct causes of heart failure on the rise, the number of patients with the condition is projected to skyrocket in the coming decades. One analysis predicts a threefold increase in hospitalizations for heart failure by the year 2050.

While many paths lead to heart failure, all who suffer from it must face the necessity of becoming actively engaged in managing their conditions. “I tell my patients that managing heart failure is really a cooperative effort between the doctor and the patient,” explained cardiologist Dr. Lisa Marie Mielniczuk. Dr. Mielniczuk is a physician with the Heart Institute’s Heart Function Clinic as well as Medical Director of the Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic and the Telehealth Home Monitoring Program.

The Effectiveness of Guideline-Based Care

A range of medical, surgical and behavioural interventions are recommended in heart failure care guidelines. The IMPROVE-HF study, released earlier this year in the Journal of the American Heart Association, looked at six of these standard treatments and showed that all substantially reduce the risk of death for patients with heart failure, measured two years after initiation of treatment. These six treatments include three classes of drugs (beta blockers, ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, and anticoagulation drugs for atrial fibrillation), implantable devices, and patient education.

The benefits of each successful treatment assessed in IMPROVE-HF were substantial: The largest came from the use of beta blockers and cardiac resynchronization therapy, which reduce the risk of death by 58 and 56%, respectively. Patient education, critical for helping patients understand the medical rationale for their sometimes gruelling medication regimens and lifestyle changes, reduces the risk of death by 27%.

The effects of these treatments appear to be cumulative, where implementing up to four or five of the treatments with a patient adds incremental benefits. The most beneficial combination examined—a beta blocker, an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, anticoagulation, and education—reduced the risk of death by an astounding 83%.

All of these treatments are standard at the Heart Institute, said Dr. Mielniczuk. “Our Heart Function Clinic offers patients the full spectrum of best-practice-based care, from aggressive medical therapy to pacemakers and devices, to mechanical support and transplants, even palliative care for patients who have reached that point,” she added. Education for patients—about dietary restrictions, fluid intake, physical activity, weight and blood pressure, medications—and subsequent telehome monitoring help keep patients on track.

Much of the care delivered today would have been considered too aggressive only a few years ago, but recent studies have shown that older patients can tolerate and benefit from intensive treatments and that some treatments thought to help only those at high risk of death benefit lower-risk patients as well. For example, the Heart Institute’s RAFT trial, published in 2010, showed that cardiac resynchronization therapy could reduce the risk of death for heart failure patients by 24% compared with the use of a standard implantable cardioverter defibrillator, including patients with mild to moderate heart failure.

“I tell my patients that managing heart failure is really a cooperative effort between the doctor and the patient” – Dr. Lisa Marie Mielniczuk, Cardiologist, Heart Function Clinic, UOHI

The Heart Institute’s Heart Function Clinic is one of the highest-volume heart failure clinics in Canada, seeing 2,500 to 3,000 patients a year. “The findings of the IMPROVE-HF trial point to the importance of disease management programs, like our Heart Function Clinic and Telehome Monitoring, for patient survival. These are things that the Heart Institute already does and does well,” said Dr. Mielniczuk.

However, many heart failure patients do not have access to such specialty clinics and academic centres. About half of all heart failure patients in Canada have a general practitioner or family physician managing their care instead of a cardiac specialist.

“Community physicians should take away from this study that evidence-based therapy works in the real world, and their patients should be on those therapies. They should also be aware that referring advanced heart failure patients to monitoring programs such as those at the Heart Institute, can help them not just with their morbidity but their mortality as well,” said Dr. Mielniczuk.

Some misunderstandings about best practices for heart failure still exist in the community, added Christine Struthers, the advanced practice nurse for the Cardiac Telehealth program. “In the last 10 to 15 years, the big changes in managing heart failure have to do with finally having medications that are now known to work. We never had these before. So the need for education that’s related to those medications is huge. Beta blockers are now known to be the medication that really improves heart function and survival, but in the past, people thought that beta blockers couldn’t be given to heart failure patients. We still have to reassure some people that it’s OK,” she said.

Empowering the Patient

Also, heart failure patients need to be taught how to be their own advocates and caretakers to prevent the unnecessary worsening of their conditions and expensive hospital readmissions. “It’s very important to empower patients so they understand why they’re taking their drugs, in a way that relates to their heart function—what actions those drugs have on the heart,” explained Struthers. “I think that’s the only way to ensure safety and ensure that patients participate in their care—to really empower them to know what medications they’re taking and why.”

A lot of misunderstanding exists about how heart failure medication works, she added. For example, patients often think that any increase in dosage means their condition is getting worse. But beta blockers have to be started at a low dose and slowly increased over time. “During that period, it’s normal for patients to feel worse than they will in the long run,” explained Struthers. “They have to be educated to expect that, or they’ll stop taking the drugs”.

Equally important to having patients understand why their medications will help is having them understand and undertake the lifestyle changes needed to manage their disease—restrictions on salt and fluid intake, increased daily activity, and an awareness of their symptoms, meaning what is normal and what is a sign of danger, said Dr. Mielniczuk.

“Medication education and self-care education both have to be done. One without the other doesn’t work very well,” agreed Struthers. And both together work very well, reflected in the nearly 30% decrease in the risk of death with education alone seen in the IMPROVE-HF.

As Struthers recounted, the clinic recently counselled a heart failure patient by phone, and he managed to lose 7 pounds of retained fluid. “He now feels great. Before talking to us, he had no idea what salt did, had no idea that he couldn’t drink an unlimited amount of fluid. Education alone had a huge impact—he did really well because of self-care.”

Patients at the Heart Institute have the advantage of access not only to specialist physicians but also nurses with specialty training in heart failure and an entire multidisciplinary care team that participates in patient education.

“We have quite a few services and strategies for these patients, and altogether we’ve seen a decrease in readmissions. I think our challenge now is to do more educational initiatives out in the community so there’s more continuity of care,” Struthers concluded.