Shortness of breath, swelling ankles, fatigue—they can easily be passed off as part of getting older. But for more than 600,000 Canadians, these are signs of something much more serious. They are among the frustratingly non-specific symptoms of heart failure, the only form of heart disease that is becoming more common.

“We are winning the cardiovascular disease war but losing on the heart failure front, in part because people are living longer with damaged hearts,” observed Peter Liu, MD, Chief Scientific Officer and Vice President of Research at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute.

It’s a paradox, said Dr. Liu—one that arises out of our success at saving people who have a stroke or heart attack, and it comes at a high cost for both individuals and the health care system.

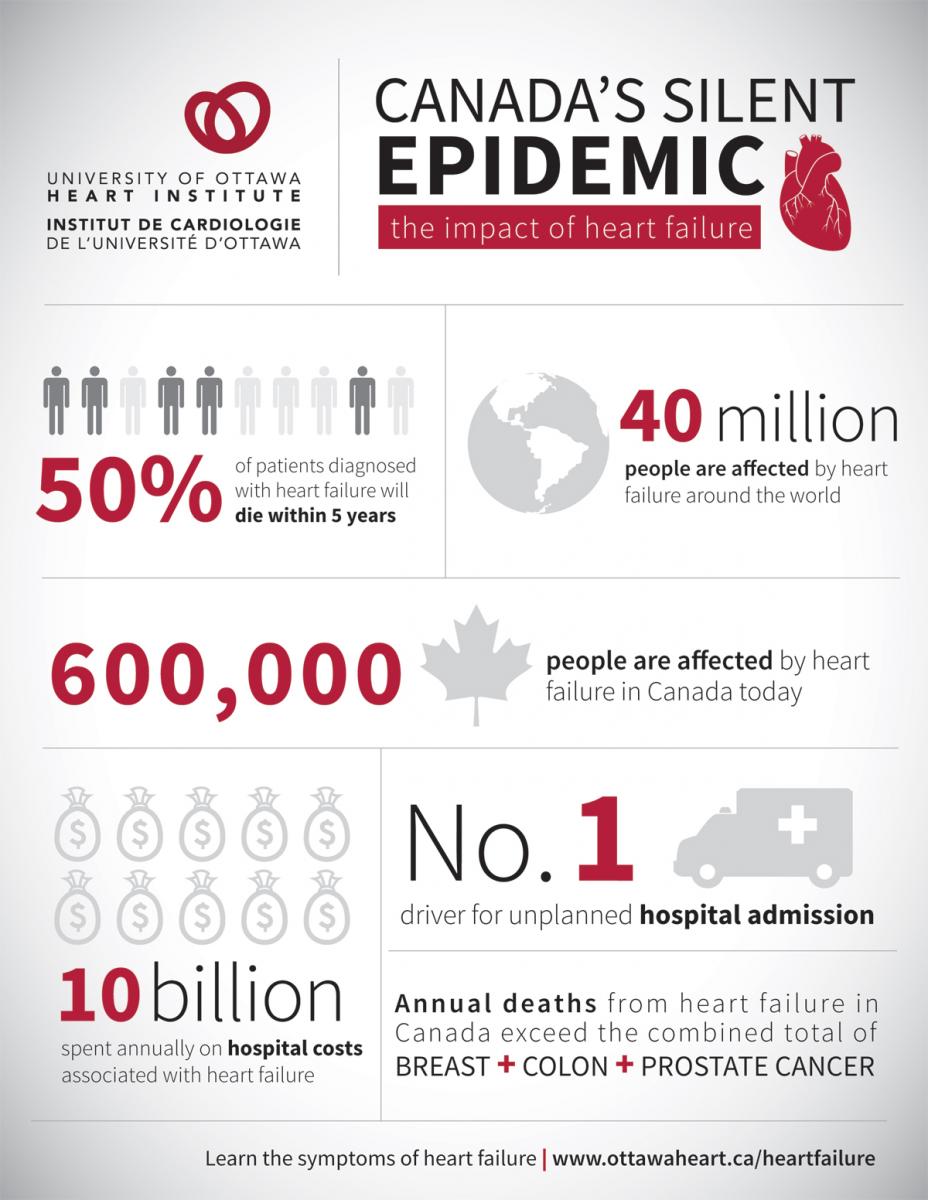

Heart failure is a complex and progressive chronic condition. One in four people with heart failure dies within a year of diagnosis and half die within five years. Annual Canadian heart failure deaths outnumber those from breast, prostate and colon cancer combined. Living with heart failure can mean a poor quality of life that makes it difficult for a person to take part in the activities he or she enjoys.

For the health care system, heart failure means more people in the hospital. It is the most common cause of unplanned hospital admissions and the most common reason for hospitalization among people ages 65 and older. The cost of that hospital care is significant—more than $10 billion a year. In fact, heart failure is the single most costly chronic disease affecting Canadians, and it is expected to affect more and more people as the population ages.

Dr. Liu refers to heart failure as a “silent epidemic,” in part because the condition can be difficult for primary care physicians and their patients to recognize until it has reached an advanced stage, but also because it has not received as much attention as other growing health care issues.

Nonetheless, advances in implantable devices and new medications offer new options for heart failure management that can reduce mortality and hospitalization. And research into ways to detect heart failure earlier has become a priority.

The Heart Institute is in the process of rolling out a new integrated strategy to improve heart failure care both within its walls and across the Eastern Ontario region it serves. The effort weaves together in-hospital care as well as tools and systems to smooth the transition of patients back to their home settings (see “Telehome Monitoring Helps Patients Help Themselves”), with support for primary care providers out in the community (see “Strengthening the Network of Care”).

“A big part of heart failure management is networking with the primary care providers,” said Lisa Mielniczuk, MD, Director of the Heart Failure Program at the Heart Institute. “Building our regional program and providing the infrastructure and tools to these providers is very important.”

Dr. Mielniczuk also noted that this regional strategy for heart failure management is a natural expansion of the Heart Team approach within the Heart Institute, which sees a multidisciplinary team of cardiologists, surgeons, nurses and other allied health professionals, such as nutritionists and physiotherapists, working closely together to provide the individualized care necessary for each heart failure patient.

The goal of these various initiatives is to keep patients out of the hospital in the first place and, when they do have to be hospitalized, prevent readmission after discharge. The result is not only improved care and quality of life for patients, but better use of scarce health care resources.

“There is a lot of uncertainty, a lot of ambivalence, a lot of fear that heart failure patients and their families have to work through,” said Dr. Mielniczuk. “One of the things we try to do at the Heart Institute is help them understand what this disease means to them, how we will treat it and what they can expect going forward.”

The good news, she added, is that many heart failure patients can return to normal or near-normal activity with treatment. “Improvement is the rule for most patients.”

This good news was front and centre in April at the Ottawa Heart Research Conference, which this year focused on “Advances in Heart Failure Management: The Science and the Art.” The conference held something for everyone, from heart failure researchers and cardiologists to primary care physicians and allied health providers to health policy innovators (see “Advances in Managing the Condition”).

The Research Conference underscored Drs. Liu and Mielniczuk’s belief that heart failure does not have to be a devastating diagnosis. The Heart Institute is making that belief a reality with its innovative programs to support patients and their care providers.

Lisa Mielniczuk, MD, Director of the Heart Institute’s Heart Failure Program attending the recent Ottawa Heart Research Conference on advances in heart failure, which she helped organize.

Read the rest of our Focus on Heart Failure series: