As we age, the aortic valve in our hearts can become hardened due to calcium deposits that build up over time. This is the most common cause of aortic stenosis which affects the opening and closing of the valve, restricting blood flow to the rest of the body. The condition affects more than 100,000 Canadians over the age of 65.

Until recently, surgical replacement was the only treatment option, but over the last several years, TAVI, or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (also known as transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR)), has emerged as a viable alternative with advantages over surgery. Because the TAVI valve is inserted through a catheter, the incision is small and recovery times can be much shorter than for the open heart surgical procedure.

First introduced in the early 2000s, TAVI is approved in Canada mostly for use in patients who are inoperable or whose condition makes surgery a high risk. As evidence for TAVI’s safety and durability grows and advanced technology comes on the market, the procedure is poised to become much more common.

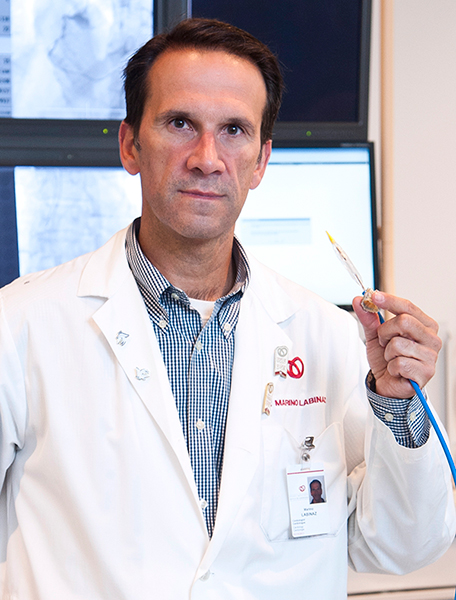

The Beat sat down with Marino Labinaz, MD, to talk about the future of TAVI. An interventional cardiologist, Dr. Labinaz leads the TAVI heart team at the Ottawa Heart Institute. They started performing TAVIs in 2007 and the Institute is currently funded by the Province for about 100 procedures per year.

Extending TAVI to Lower Risk Patients

“We do patients for whom surgery would be high risk, often higher risk patients than at other centres in the province,” said Dr. Labinaz. “It has always been the philosophy of the Heart Institute to be fairly inclusive with our therapies. We still get some complex patients referred from other TAVI centres that they don’t want to do themselves.”

The older and sicker high risk patients require hospital stays similar to surgical patients. In Europe, where TAVI is used in a broader range of patients, the time in hospital can be much shorter.

“In low risk patients, we are seeing expedited discharge. There is a trial underway in Vancouver where they are looking at 24-hour discharge,” he said. “Where I see the sweet spot for TAVI in the low-risk patient is in rapid recovery. You’re going to come in, get your TAVI and go home the next day. In our patients, we haven’t reaped the benefit of early discharge yet.”

“The use of TAVI in these patients will be, in part, patient choice. It may also become a societal choice,” he continued, “Because, if you can send a patient home in 24 hours, then TAVI could become very cost effective when compared to a five- to seven-day stay for surgery. This will particularly be true if the cost of the valves comes down.”

TAVI is currently a more expensive option than surgery due to the cost of the valves, but as demand for TAVI grows and as new vendors enter the market and increase competition, costs are expected to decline.

A large clinical trial to be presented at the annual American College of Cardiology conference in April will provide a look at TAVI outcomes in medium risk patients. “I expect the results will be very good,” said Dr. Labinaz, “A low-risk trial is now starting in the US. This will look at TAVI for the bread-and-butter surgical patients.”

It’s my prediction that TAVI will become a standard way of doing aortic valve replacement in the next five years.

-- Marino Labinaz, MD

Conscious Sedation Over General Anesthetic

Another emerging benefit of TAVI over surgery is the use of conscious sedation.

“Currently, we give patients a general anesthetic and they are intubated. Conscious sedation means we give them short-acting medication,” he explained. “They are conscious, and they are never intubated. The patient doesn’t have the issue of the anesthetic to recover from, and it saves time so you can do more patients in a day.”

Given the Heart Institute’s emphasis on high-risk patients, conscious sedation is only just getting started in Ottawa.

Improved Technology

One of the limitations of TAVI is the size of the catheter. To fit the valve inside, the catheter has to be larger around than those used in angioplasty for delivering stents.

“From a patient perspective, one of the biggest changes is that the valves are becoming smaller in size,” said Dr. Labinaz. “The first generation devices were very large calibre and we would see higher rates of dissections or occlusions in the arteries. Smaller tubes mean fewer vascular complications.”

“They aren’t yet commercially available here, but there are three valves available on special access from Health Canada that have the ability to be retrieved,” he said. “With two of them, you can deploy the valve to 80% to get an idea how it is positioned and functioning, and then retrieve it. The only completely deployable valve that can be retrieved is the new Lotus valve. We will begin using it this spring.”

“Another advance related to leaking is the addition of flexible sleeves on the outside of the valves that provide a better seal with the calcium and nodules and crevices that can create an uneven surface. Preliminary data is positive.”

One complication of aortic valve replacement that’s common to surgery and TAVI is stroke. Material from the calcium deposits in and around the valve can break away during the procedure and travel up the bloodstream to the brain. For both surgery and TAVI, the rate of stroke is 5 to 10%. On the horizon for TAVI is the use of protective filters in the blood vessels to capture that material. Results so far have been mixed.

Looking Ahead

“TAVI has been a real game changer,” concluded Dr. Labinaz. “We’re getting lots of data now on the durability of the valves in people who have had them for five and 10 years. They have low failure rates and seem to be comparable to the surgical valves.”